Printed in the Spring 2021 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Watts, Alan, "The Cosmic Dance" Quest 109:2, pg 22-23

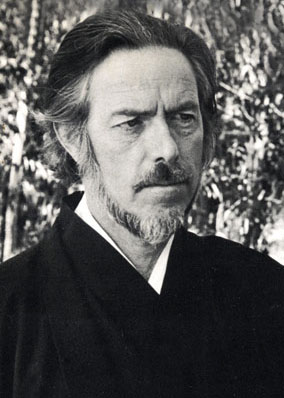

By Alan Watts

Alan Watts is one of the world’s most popular interpreters of Eastern philosophy for a Western audience. Originally published in 1963, The Two Hands of God: The Myths of Polarity is Watts’s forgotten book on world mythology—myths of light and darkness, good and evil, and the mystical unity that sees the transcendent whole behind apparent opposites.

Fans of the mythologist Joseph Campbell will immediately notice his influence throughout this book. Campbell and Watts were in fact friends during its writing, and Campbell shared notes and feedback on several chapters. One might even say that The Two Hands of God is Watts’s own introduction to the mythology of the world’s religions, using the nondual lens for which he was so well known in his Zen teachings and study.

As there is no woven cloth without the simultaneous interpenetration of warp and woof, there is no world without both the exhalation and inhalation of the Supreme Self. Though the image of breathing, as distinct from weaving, makes the two successive rather than simultaneous, nevertheless the one always implies the other. Successive in time, they are simultaneous in meaning, that is, sub specie aeternitatis, from the standpoint of eternity. Beginning and end, birth and death, manifestation and withdrawal always imply each other. In Western—that is, Judaic and Christian—imagery there has generally been a tendency to overlook this mutuality and to see each life and the creation itself as unique—as a beginning, and then an end which does not imply another beginning. Our world is linear, and the course of time is very strictly a one-way street. Nature is a clockwork mechanism which does not wind itself up in the process of running down. In Western religion and physics alike, we tend to think of all energy as expenditure and evaporation. There is no hope for a renewal of life beyond the end unless the supernatural Creator, by an act of special grace, winds things up again.

As there is no woven cloth without the simultaneous interpenetration of warp and woof, there is no world without both the exhalation and inhalation of the Supreme Self. Though the image of breathing, as distinct from weaving, makes the two successive rather than simultaneous, nevertheless the one always implies the other. Successive in time, they are simultaneous in meaning, that is, sub specie aeternitatis, from the standpoint of eternity. Beginning and end, birth and death, manifestation and withdrawal always imply each other. In Western—that is, Judaic and Christian—imagery there has generally been a tendency to overlook this mutuality and to see each life and the creation itself as unique—as a beginning, and then an end which does not imply another beginning. Our world is linear, and the course of time is very strictly a one-way street. Nature is a clockwork mechanism which does not wind itself up in the process of running down. In Western religion and physics alike, we tend to think of all energy as expenditure and evaporation. There is no hope for a renewal of life beyond the end unless the supernatural Creator, by an act of special grace, winds things up again.

But the Indian view of time is cyclic. If birth implies death, death implies rebirth, and likewise the destruction of the world implies its recreation. The Western images are thus essentially tragic. Nature is a fall and its goal is death. There is no necessity for anything to happen beyond the end: only divine grace, operating outside the sphere of necessity, can redeem and restore the world. But the Indian imagery makes the world-drama a comedy—a sport or lila—in which all endings are the implicit promise of beginnings. Yet comedy must always depend on surprise. The burst of laughter is our expression of relief upon discovering that some threatened doom was an illusion—that “death was but the good King’s jest.”

Consider a very simple but typical comedy enacted many years ago in a London music hall. The curtain rises upon an elaborately furnished bedroom. The sleeper is at once awakened by a shrill alarm clock. Reaching under his pillow, he produces a hammer and smashes it in the face. Sitting up in bed, he glowers at his early-Monday-morning surroundings, and, hammer still in hand, slowly crawls out from the covers. Thereupon he proceeds, item by Victorian item, to smash everything in the bedroom—the bedside table, the flowered pitcher and basin on the wash stand, the knickknacks on the mantel, the chocolate-colored chamber pot patterned with green leaves, the glass on the pictures, the windows, and the bed itself—leaving only a bulbous and pretentious floor lamp with a huge glass shade. Creeping stealthily across the wreckage he eyes this last and perfect object of his rage, very obviously designed to disintegrate with a spectacular explosion. Instead of smashing it with his hammer, he grasps it with both hands and flings it high into the air—and, falling to the floor, it bounces: made of rubber.

This is the vulgar archetype of the cosmic punch line, the totally unexpected anticlimax which, in Hindu mythology, follows the terrifying tandava—the dance in which ten-armed Shiva, wreathed in fire, destroys the universe at the end of each cycle. But Shiva is simply the opposite face of Brahma, the Creator, so that as he turns to leave the stage with the world in ruin, the scene changes with his turning, and all things are seen to have been remade under the cover of their destruction.

The polarity of Brahma and Shiva thus finds its expression in what at times seems to be the extreme ambivalence of Hindu culture—extreme in its asceticism as in its sensuality. On the one hand, there is the goal of Yoga, the meditation-discipline: to concentrate thought so as to penetrate and burn away the illusion of the world. Yoga is thus man’s participation in the inhalation or withdrawal of the world breath, in the dissolution of maya, and in return to the undifferentiated unity of the Godhead. Shiva, the destructive aspect of Godhead, is therefore the archetypal yogi, the naked ascetic daubed with ashes sitting hour after hour with his consciousness in total stillness. On the other hand, there is that exuberant delight in form and flesh which is so exquisitely celebrated in Hindu dancing, music, and sculpture, in the marvelously refined eroticism of the Kamasutra, the scripture of love, as well as in the vision of the perfectly governed society laid out in the Arthashastra, the scripture of politics. One might almost say that India had set herself the problem of exploring these two attitudes to their extremes and then of finding the synthesis between them.

This problem, stated in mythological terms, is the recurrent theme of a type of popular Hindu literature known as the Puranas. Certainly much later than the Upanishads, these are texts of uncertain date, forming a repository of myth and legend accumulated over many centuries. Notable in the Puranas is the relationship of the gods to their feminine counterparts or shaktis, the feminine symbols of maya, the world-illusion, whereby the male god is alternatingly seduced and disenchanted. Originally the Godhead is hermaphroditic, beyond the opposites, but at the moment of creation the feminine shakti leaps forth spontaneously, as Eve was created from the body of Adam while he slept.

Alan Watts (1915–73) was a British-born American philosopher, writer, speaker, and counterculture hero, best known as an interpreter of Asian philosophies for a Western audience. He wrote more than twenty-five books and numerous articles applying the teachings of Eastern and Western religion and philosophy to our everyday lives.

Excerpted from the book The Two Hands of God. Copyright © 2020 by Joan Watts and Anne Watts, © 1963 by Alan Watts. Reprinted with permission of New World Library.